Staff Notes #2

Staff Notes

design

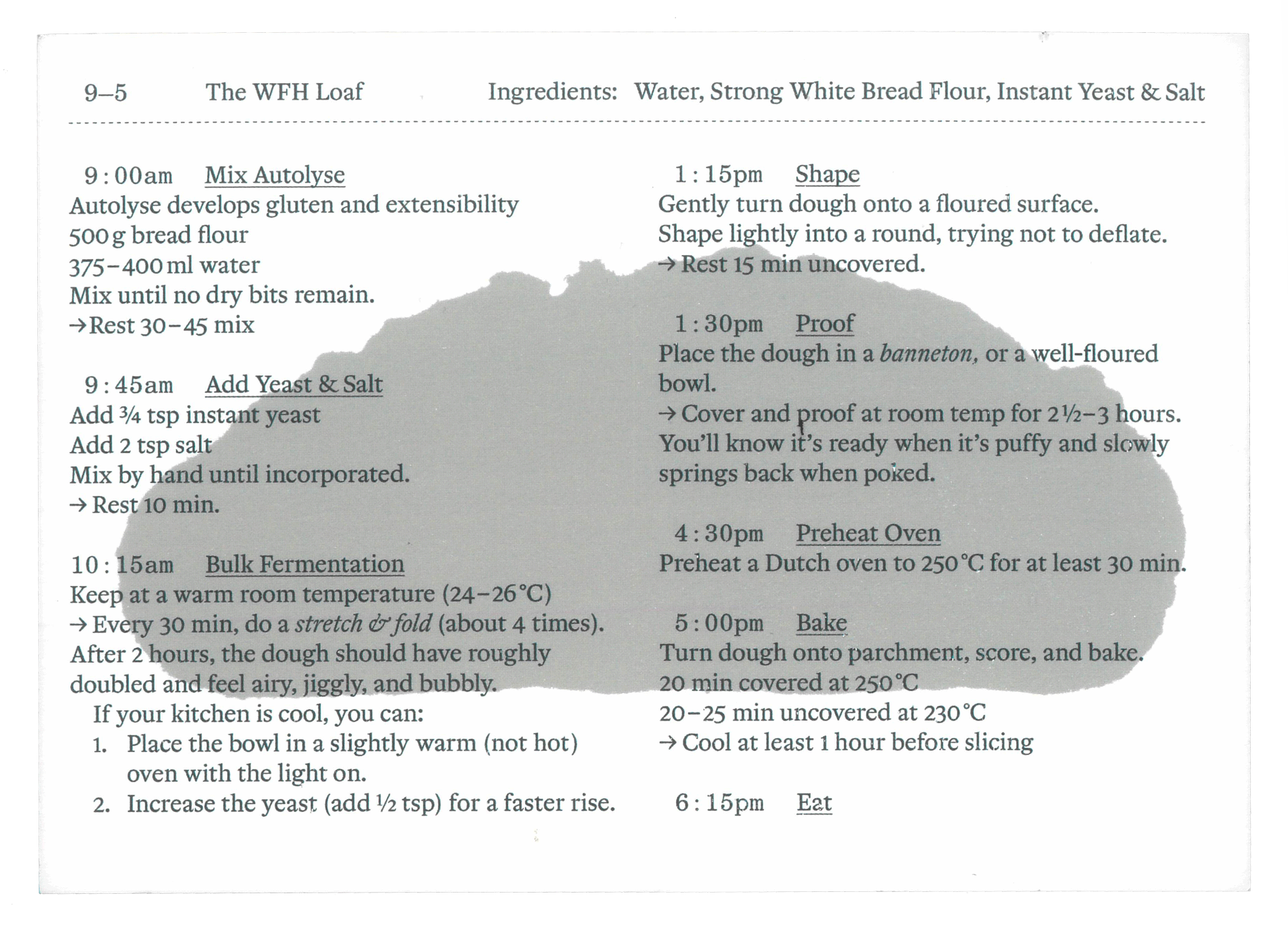

The Work from Home Loaf

You wake up before the alarm. It was five minutes at first, but now it’s closer to fifteen, even on weekends, even on the days when you’re not technically at work. You’re scrolling the news, the apps, and then you’re up out of the blue light into the kitchen. You needed to piss so it’s 8:00 by now, and you’re getting down the big Pyrex bowl from the cupboard. The bowl is heavy in a reassuring way, but you have no idea where it came from, and can’t remember buying it. You pour some water into the kettle, a little too much, and think of your parents and how they said this would happen eventually. The waking, forgetting, urinary aspects of the years under your belt.

There is yoghurt in the fridge, sliced bread in the freezer, and a dishwasher full of mostly clean plates. You think to yourself that dishwashers are the best thing since sliced bread. Instead of unloading the whole thing you take just one plate out and place it next to the bowl on the counter. You take a slice of frozen bread out of the freezer and place it in the toaster, waiting for the kettle to finish boiling before turning it on. You wait because you’re unsure how the fusebox works, and aren’t in any particular rush today. Not yet. So by the time it’s 8:10 there’s toast, coffee, a little water left, and the possibility of some yoghurt if that doesn’t do it. And while the coffee cools and the butter softens, you open another cupboard and take out the tightly-packed bag of strong-white flour.

The bag is one kilogram and you need only half that, so you don’t bother with scales and eyeball it into the bowl. Out comes the measuring jug, also Pyrex, and into that goes 300ml of cool water, plus another 75ml from the kettle. You remember getting the jug from a cornershop on the high street near your old flat, and place the tip of your finger inside to check the water’s lukewarm-ness. The water goes into the bowl and now you’re mixing with a spoon, then your hands. You feel grateful for the kettle, the bowl, the jug, the dishwasher. A few minutes of this and the flour and water are incorporated. They're dough. You cover the bowl with a tea-towel.

It takes some time to eat breakfast, up to around 8:50. And why rush? This is called the autolyse method, where flour and water are mixed and allowed to rest before other ingredients are added in. Returning to the kitchen you take the dough out of the bowl, and add two teaspoons of table salt to it, gently working the crystals through the mixture. Once incorporated, you add close to a teaspoon of dried active yeast. Mix, bowl and cover. These are all the ingredients you will need.

Now it’s 9 o’clock which means the world is awake. You check The Guardian to make sure nothing new has happened in the last hour. You check your emails. You check the Financial Times. You read an article about the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the ‘productivity crisis’, and the inability of the civil service to produce accurate forecasts. You send an email and decide to check on the dough. Forty minutes have passed and there’s a little rise in the mixture, the magic of hydration, fermentation, gluten development, and those things you’ve forgotten from your Home Economics classes.

You splash a little water on your hands and lift one edge of the soft, sticky dough from the bowl, folding it back over itself. You spin the bowl a quarter-turn and repeat this three more times. You leave it to rest for another 30 minutes. You send another email and open the document you’re planning to work on today.

In the Covid lockdown you – like many others – had begun a sourdough starter. The houseplants had shrugged while you fed it, burped it, and convinced yourself that you could make the best of a difficult situation. You could change your habits, walk at least 30 minutes a day, look after your things, look after other people. You had received money from the government – on the ‘furlough scheme’ – and spent a small amount of it on a 16kg sack of bread flour. This all seems ridiculous now. The starter had died almost as soon as you had gone back to your job, and with it, the idea that a daily routine might be defined by anything other than work. The rest of your furlough money had been spent on rent.

In the kitchen, stretching and folding the dough for a fourth time you think of all the sourdough starters sitting lifelessly in the back corners of fridges across London. The dough in your hands is bubbling now, aerated with the active dried yeast, with the folds and gentle warmth of the countertop. You added the teaspoon of yeast for this reason – as a compromise – to time the rising and fermentation of the dough with your lunch break. Soup.

It’s just after 1 o’clock in the afternoon, so you tip the dough out onto a floured surface. It looks a little wet, but using a bench scraper – and some extra flour – you manage to shape it into a rough rugby ball shape. Your soup is out of the tin and in the microwave at this point, so you leave the dough to rest while you extract it, and eat at your desk. You’re eating and emailing for 15 to 20 minutes. And when you return the dough is relaxed and ready for a final rise: a ‘proof’. You dust a linen cloth with rice flour and place the dough inside it, and then this dough-filled cloth inside a banneton – a type of wooden basket made just for this purpose.

Proofing takes at least 2-and-a-half hours, and is the make-or-break moment of the day. The final sprint. You pour more coffee and realise that you have achieved nothing of significance up to this point. You have simply sent emails, made notes to yourself and anxiously refreshed the websites of news organisations. Emails aren’t work, notes aren’t work, and checking the news certainly isn’t work. You have tentatively shuffled words around a document. Is this work? You have styled these words with different typefaces and thought carefully about their size, their orientation, the spaces between them. Is that work?

Generally, you enjoy working from home because it feels like a compromise. You can steal time back in the kitchen, the dishwasher, the shower – the commute and cooler talk substituted for domestic appliances, housework and exercise. You feel that the prerequisites of productivity are to be clothed, washed and fed – to be healthy – and are aware that the statistics which measure it fail to take these essential facets of life into account. That there is no neutral definition of productive and unproductive labour. That the shift to a digital service economy has complicated these ideas.

None of this awareness helps you feel productive, which is ultimately what you’ve learned to want more than anything else. For an hour you helplessly flick between documents, and for another you sit in an online meeting, through which you remain largely silent. You rub your eyes and catch the gentle scent of fragranced soap, rice flour, and the yeast at work next door. When the meeting is over you return to the kitchen – around 4:30 – and quickly turn the oven to 250°C, as hot as it will go.

Inside the cooker you place a heavy Dutch oven to pre-heat. It is a bright orange name-brand you received as a present during lockdown, an expensive form of encouragement from your parents. You think of them again, and of visiting when work dies down. You check the news. You save, exit and return to the kitchen for the final step.

Carefully, you lift the dough – now doubled in size – from the basket onto a sheet of baking paper. You take the Dutch oven from the cooker and drop the dough inside, feeling the danger of the heat radiating from its inner walls. Lid attached, you place the pot in the cooker and wait 40 minutes, adjusting the heat down to 220°C and removing the lid half-way through.

It is quarter-to-six now, and the working day is over – another you will never get back. You lift the bread from the oven, flipping it over and laying it on the counter. You take a long wooden spoon from the dishwasher and tap the base of the loaf.

It makes a hollow sound.

This article was written for the termly publication – Staff Notes – for staff and students on the Graphic Design programme at Camberwell College of Arts. SN is edited by myself and amy etherington.