Notes on Aby Warburg

Tactics & Strategies in the Digital Archive

notes

Notes for the book Aby Warburg and the Image in Motion by Philippe-Alain Michaud (translated by Sophie Hawkes) with a forward by Georges Didi-Huberman. Published (2004 [1998]), by Zone Books.

Foreword

(by Georges Didi-Huberman)

A key question motivates Didi-Huberman’s foreword (and, by extension, Michaud’s book): How to move Warburg out of the space to which he has been consigned – of “reference-reverence” – of secondary importance in ‘serious’ debates on art history? How to recognise Warburg as the originator of an ‘iconology’ formed through the ‘Germanic context of Kulturwissenschaft’ (over Panofsky’s Anglo-Saxon ‘social history of art’)? (p.8)

Contemporary accounts of Warburg‘s life and work tend to centre his ‘erudition’ – his “use of textual sources and archives, his prosopography” – wheras this account, from Michaud, holds on instead to the idea of movement: “...both as object and method, [...] a characteristic of works of art and a stake in a field of knowledge claiming to have something to say.” (p.9)

In this sense it is preoccupied – and periodizes Warburg’s pracice – with motion across three ‘journeys’:

- The historical journey toward the ‘image of motion,’ (e.g. the “‘survival’ of gestural expressions from Antiquity”) through historic forms of art.

- The more wide-ranging ‘image-motion’ (or ‘movement-image’ subsequently theorized by Deleuze). Here, historical concerns become geo- and ethnographic, as in Warburg’s journey to New Mexico, and Antiquity in some way ‘comes alive’.

- The journey to Hamburg, the establishing of his institute which seeks to reintepret art history as a knowledge-movement of images: “a knowledge in extensions, in associative relationships, in ever renewed montages, and no longer knowledge in straight lines, in a confined corpus, in stabilized topologies.” This is typified by the Mnemosyne atlas. (p.9–10)

It is in this way that Warburg ‘sets art history in motion’, both by articulating a concern with motion as such (over, for example, static ‘poses’), but also by ‘setting into motion’ the discipline itself. “From now on [...] we shall have to imagine what art history might become, with Warburg, in the age of its reproduction in motion.” (p.12)1

Through this Warburg is able to take a perhaps ‘dangerously’ kaleidoscopic view of art history’s subject matter, “to gain access to a world open to multiple extraordinary relationships”:

“... this excess no less than this access contains something dangerous, something I would call symptomatic. Dangerous for history itself, for its practice and for its temporal models: for the symptom diffracts history, unsettling it [...], it is in itself a conjunction, a collision of heterogenous temporalities (time of the structure & time of the reading of the structure)” (p.12)

This ‘excess’ generates a kind of ‘knowledge-montage’ which “rejects the matrices of intelligibility” – rejects an evolutionary, ‘positivist’ or teleological approach to the discipline – and instead recognises that “...[the] image is not a closed field of knowledge; it is [instead] a whirling, centrifugal field...” (p.13)

However, there are risks with this approach. Complicating Panofsky’s reassurance that art history is a ‘humanist discipline’, Warburg surrenders himself to the (Nietzchean) possibility of a ‘complete loss of self’; to the question of pathos and pathology. (p.13-14)

Some interesting questions here from Didi-Huberman:

- “Is art history prepared to recognize the founding position of someone who spent almost five years in a mental institution...? Someone who ‘spoke to butterflies’ for long hours [... whom doctors] had no hope of curing?”2

- “Must one [...] speak of Warburg’s art history as a ‘pathological discipline’?”

- “Was not speaking to butterflies [...] the definitive way of questioning the image as such, the living image, the image-fluttering that a naturalist’s pin would only kill?”

- “Was it not to recover, through the survival of the ancient symbol for Psyche, the psychic knot of the nymph, her dance, her flight, her desire, her aura?” (p.14)

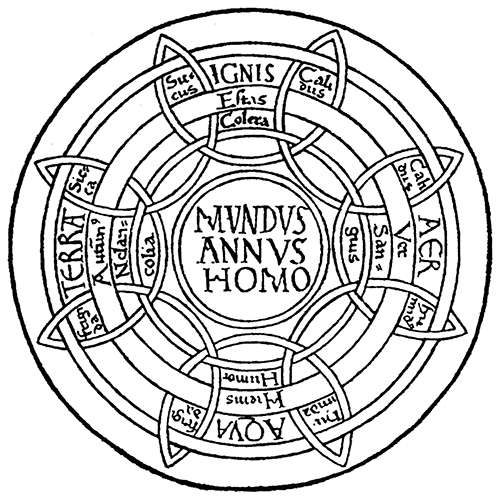

As an aside, I will note here the emblem of the Warburg Institute.3

“Warburg, for his part, never ceased to rethink the questions, and this caused him to rework the whole body of his thought each time, reorganizing it, opening it up to new fields.” (p.14)

What can be learned from the concept of ‘pathology’, what is useful in it for us? Didi-Huberman approaches this in two ways:

- Just as Nietzsche enters philosophy through the door of the “birth – and survival – of tragedy”, Warburg enters art history through the “renaissance – or survival – of Antiquity”. This theoretical relationship to Nietzsche shows, perhaps, the Dionysian sensibility present in Warburg’s work: his reinscription of ‘pathology’ through the ‘Pathosformel’ (the pathos formula) as an “archaeological science of the pathos of Antiquity.”

- This Pathosformel as a means of interpreting the ‘symptom’ – which Warburg understood as a “movement in bodies”, a ‘passionate agitation’ – that works as a “visible expression of psychic state that had become fossilized [... in images]”4 In this way Warburg went beyond a medical definition, understanding ‘symptoms’ not as “‘signs’ (the sēmeia of classic medicine)” but as something akin to ‘unconcious memory:’ “...their temporalities, their clusters of instants and durations, their mysterious survivals...”(p.15-16)

Perhaps we can characterise these approaches as either archaeological or anthropological, or each an intersection of the two? This is the anachronicistic nature of Warburg’s method or Pathosformeln: “It includes jumps, cuts, montages, harrowing connections. Repetitions and differences...” It sets art history in motion because “...the movement it opens up comprises things that are at once archaeological (fossils, survivals) and current (gestures, experiences).” Postage stamps ‘taken with’ (which is to say ‘comprehended’ alongside) bas-reliefs... (p.16-18)

“...it is a matter not only of incarnating the survivals but also of creating a ‘living’ reciprocity between the act of knowing and the object of knowledge.” (p.18)

In this way, through his archival work, Warburg seeks – like Walter Benjamin – to restore the ‘timbre of those unheard voices’ across Antiquity (and into the present moment) not simply through reproduction, but by setting himself in motion; “[displacing] his body and his point of view” such that this ‘unconcious vision’ might at last be seen. (p.18)5

Footnotes

-

There is a point here to make about Benjamin, the ‘thought-image’ in Theses and the ‘Work of Art...’ ↩

-

A fascinating insight here from the Warburg Institute: Aby Warburg’s ‘Bienentanzbrief’ ↩

-

From the Warburg Institute: The emblem, which appears above the door of the Institute, is taken from a woodcut in the edition of the De natura rerum of Isidore of Seville (560-636) printed at Augsburg in 1472. In that work it accompanies a quotation from the Hexameron of St Ambrose (III.iv.18) describing the interrelation of the four elements of which the world is made, with their two pairs of opposing qualities: hot and cold, moist and dry. Earth is linked to water by the common quality of coldness, water to air by the quality of moisture, air to fire by heat, and fire to earth by dryness. Following a doctrine that can be traced back to Hippocratic physiology, the tetragram adds the four seasons of the year and the four humours of man to complete the image of cosmic harmonies that both inspired and retarded the further search for natural laws. ↩

-

Here Didi-Huberman is borrowing the analysis of Gertrud Bing ↩

-

A thought here about the question of the ‘totality’ – the ‘cognitive map’ from Jameson? ↩