Towards a Minor Etymology

MA Art & Politics

article

Towards a Minor Etymology: Counter-mapping the Immaterial Violence of Financialization – an essay for the Masters module Counter-mapping the Politics of Space supervised by Dr David L Martin

0. Introduction

In this essay I will ask two interrelated questions: What is at stake in the production of language? and What is at stake in the language of production?

The first question seeks to identify a framework for identifying and discussing the ways in which language acts as a political and perhaps even a material force in the world. Production here is meant in two senses, both the singular act of speech (the production of a word or phrase) and also the production of a shared communicative, or non-communicative, system which changes over time (such as the English language). To do this I will examine the work of key 20th Century philosophers such as Saussure, Chomsky, Deleuze & Guattari, and Foucault, as well as exploring their particular influence on the linguist Jean-Jacques Lecercle.

The second question seeks to mobilise this understanding of language within a specific domain: finance. In this question ‘production’ takes on an economic sense, with a focus on how language is enlisted in processes of financialisation. Exploring a ‘minor,’ ‘rhizomatic’ history of the term currency, I hope to demonstrate both: how etymology can be used as a methodology for creating counternarratives or countermaps of historical and contemporary political issues; and, more specifically, how processes of financialisation serve to further instrumentalise the role of language in social, political and economic life.

1. What is at stake in the production of language?

a. order-words, rhizomes & major languages

For post-structuralist philosophers Gilles Deleuze & Felix Guattari “[language] is made not to be believed but to be obeyed, and to compel obedience” (1987, p. 88). Language is not so much a direct means of transmitting information or facilitating communication (which a conventional linguistic understanding might articulate), as an indirect mode of creating order and exerting force. In their pragmatic theory of linguistics – building on work from J. L. Austin (1962) and William Labov – Deleuze & Guattari conceive the order-word 1 as the ‘elementary unit’ of this kind of language (1987, p. 88). In simple terms, “... for a pragmatics of the order-word, what is said is subordinate in importance to, and entirely dependent on, what is being done in saying it” (McClure, 2001, p. 95). In Austin we might think of this as correlative to the illocutionary act, “i.e. [the] performance of an act in saying something as opposed to performance of an act of saying something” (Austin, 1962, p. 99). Think of the phrases ‘I do’ or ‘You are sentenced…’ For Deleuze & Guattari order-words define this immanent relation between statements and acts – otherwise called implicit or nondiscursive presuppositions 2 – in particular, acts that are linked to statements by social obligation (1987, p. 91). In this way order-words take form not only in commands but also questions, promises and even the structure of grammar itself, they write: “[a] rule of grammar is a power marker before it is a syntactical marker” (1987, p. 88).3

This approach differs from the structural linguistics of Saussure and the scientific linguistics of Chomsky, against whom Deleuze in particular is opposed. These linguistic approaches focus not so much on the material effects of speech as the syntactic rationalisation or structuration of a fixed langue (in Saussure) or competence (in Chomsky) – such models are established so as to render language a properly scientific object of study which can then be used to make claims on the ‘constant, ideal truth’ of language or, perhaps more provocatively, the mind (Grisham, 1991).4 In contrast Deleuze & Guattari are less interested in the question of what language is than in what cases, where, when and how language functions (Grisham, 1991, p. 44) – their criticism of such linguistic models lies in a failure to “[connect] a language to the semantic and pragmatic contents of statements, to collective assemblages of enunciation, to a whole micropolitics of the social field” (1987, p. 6). It is in this sense that theirs is a pragmatic understanding of language – a term usually reserved for that which resides outside linguistic study – their interest lies in the position of language in a relation of power rather than a system of representation or signification; in what precedes the linguists work or remains once they are done (Lecercle, 1990; Grisham, 1991). 5

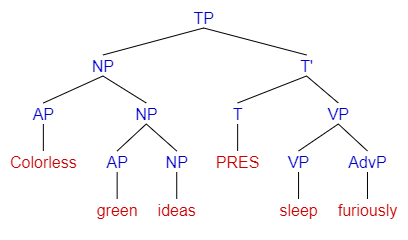

Insofar as Deleuze & Guattari define language at all, they do so as “a map, not a tracing” (1987, p. 89). For them, the concept of a map relates to “performance, whereas the tracing always involves an alleged ‘competence’...” a term, again, borrowed from Chomskyan linguistics (1987, p. 12). In line with their critique of structural or scientific linguistics outlined above, the tracing is a tool which seeks to organise, stabilise, and neutralise radical potentialities (or multiplicities) along axes of significance and subjectification, (1987, p. 13) most often through the arborescent image of the root or tree [fig.1]. We can think of this as concomitant with Foucault’s concept of the order of discourse, 6 through which every society seeks to control, select, organise and redistribute the production of discourse in order to “ward off its powers and dangers, to gain mastery over its chance events, to evade its ponderous, formidable materiality” (1971, p. 52).

Figure 1. A tree diagram for Chomsky's 'colorless green ideas sleep furiously'.

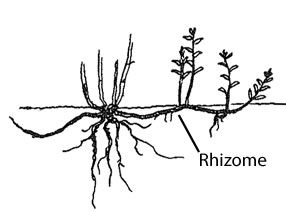

Figure 2. A diagram of a rhizomatic root structure

The performativity of the map is, unsurprisingly, counterposed to the fixity of the tracing. In line with the ‘formidable materiality’ of discourse, this language-map is “entirely oriented toward an experimentation in contact with the real” (1987, p. 12) and it forms this contact through the image of the rhizome (as opposed to the root of the tracing) [fig 2.]. The rhizome) is an important image of thought in Deleuzoguattarian philosophy, and provides a dynamic (if somewhat abstract) structure for understanding the nonlinear and networked nature of language and its ongoing formation within both micro- and macro-political structures of power.

A fundamental characteristic of the rhizome as an organisational principle – and of the map which it produces – is its openness and generativity, the multiple, proliferating entryways through which one can both enter and take flight. In this way, the map of language(s) supersedes the tracing(s) of linguistics; the latter being always only a subset of the former, a way of blocking certain entryways and producing specific impasses.7 And yet, it is these tracings that constitute the dominant orders of discourse, that codify the order-words of a major language – the acceptable or proper language of scientific reason, of linguistics, of the judiciary, the academy, the psychoanalyst's couch or the economy.

b. subjectification, violence & the remainder

It is through these blockages, in its major or reterritorializing mode that “language is involved in producing subjectifications” (Grisham, 1991, p. 51). In the same way that the tracing produces a fixed image of the map, practices of subjectification produce fixed subjectivities within the ‘rhizome of the unconscious’. Useful within this understanding is Foucault’s concept of power, construed not as the direct application of force, but instead as the force of indirect action – power which “acts upon an action” (Foucault, 1982, p. 789) – which has the ability to transform individuals into subjects.8 This form of power permeates daily life, it is the ‘conduct of conduct’ that determines one’s position within society, one’s discipline, one’s language and, ultimately, one’s obedience to that which one is subject (the state apparatuses of Althusser (1970), for example).

It is precisely this form of power that is invested in the order-word – “the word or phrase that arranges social bodies and demands obedience” (Grisham, 1991, p. 46). The phrasal order-word, ‘I sentence you…’ is an extreme example of the incorporeal transformations that are afforded by such linguistic power; in this case no-one need move, nor anything else happen, for the body of the accused to morph into the body of the convict (Grisham, 1991, p. 45). However, this force of language is inscribed into even the most banal conversations, as Lecercle makes clear in his writing on the subject: “I fight with words in order to compel my opponent to recognize me and to adopt the image of myself I wish to impose on him. [...] One becomes a subject by acquiring a linguistic place and imposing it on others” (1990, pp. 252–257).

Lecercle understands this mechanism within language as part of his broader ‘rag-bag’ theory of the remainder. The remainder is a useful term as it brings much of what we have already outlined together under a single conceptual framework; coined from its aim to bring that which remains left out of modern linguistic theory into an account of language, it positions itself as a rhizomatic ‘frontier’ between language and the world (1990, p. 229). The remainder therefore works to account for forms of subjectification enabled by language, for the violence, functionality and materiality of language, in a way that structural or scientific linguistics cannot.

Within the framework of the remainder, if language can be rendered an object of study at all, it is only as an essentially ‘historical object’9 (1990, p. 110) – the remainder is a rhizome, a map which constitutes past social contradictions and struggles within language and anticipates future ones; it is, as Lecercle says, “the part of language which conserves the past” (1990, pp. 182–183). What it means to construe a ‘linguistic place’ (or to have one constructed on one’s behalf) is then also a sociohistorical activity, and one which is therefore necessarily collective or pre-individual.10

Here we find a redetermination of the phrase, attributed to Lacan, that ‘language speaks the subject’, that “...when the subject speaks, it is always also, or always-already, language that speaks” (Lecercle, 1990, p. 103). It is in this sense that, for Deleuze and Guattari, the order-word is characterised partly by its redundancy; “the manner in which language is repeated throughout the social field, such that it is without origin in individual minds” (Bryant, 2011; 1987, p. 97). Lecercle takes this idea up within the remainder, most clearly in his analysis of how processes of linguistic change necessarily mythologize and anonymize those who coin terms or phrases (1990, p. 70). Taken to its extreme it is such processes of repetition and anonymisation that begin, for Deleuze and Guattari at least, to undo the subject entirely (1983, p. 18, 1987, p. 151).11 Instead we are left with collective assemblages of enunciation12 (the shared, pragmatic language of order-words) which command machinic assemblages of bodies (such as that of the accused-convict).

While we do not necessarily need to go so far in our claims, this intervention is useful in highlighting the instability of language's role in processes of subjectification: as a historical process enacted and contested in the present, both synchronic and diachronic; at once individual and collective; ‘immaterially material’. As evidenced in both the case of the accused-convict and the anonymous-coiner, the processes which establish one's name may just as easily render one anonymous.

c. minor languages, pass-words & levelution

This may seem a pessimistic account of language, but it hinges on a profound ambivalence already present in Deleuze and Guattari’s initial account of the order-word (McClure, 2001, p. 129). As we have seen, when used in the service of a major language (that is to say, a collective assemblage of enunciation geared towards standardisation, significance and subjectification) order-words become a means of effecting incorporeal transformations as a kind of ‘little death sentence’ or judgement, an impasse.13 However, major languages imply a minor to which they are counterpart; such minor languages are not an opposed category of language, but rather the same language perceived from a different point of view – not via the universalising gaze of the grammarian but rather from within the experimental social contexts that gives rise to a language’s continuous variation (McClure, 2001, p. 191). Together they constitute a ‘continuum of dialects’, co-located by the relations of force held between them (Lecercle, 1990, p. 186).

It is from within such minor contexts that order-words may become pass-words; a means of passage, of flight, from the imposed tracing of a major language into the vaster rhizome of the remainder. For Deleuze and Guattari the capacities of all words are therefore twofold – on the one hand a composition of order, on the other a component of passage (1987, p. 128). The force of the former is derived from its desire for striation, subjectification or reterritorialization (as outlined above) whereas that of the latter is formed in its desire for corruption, the “inclusive disjunction of contrary instances and impulses” (McClure, 2001, p. 128).

Lecercle speaks at length about corruption, adopting this technical linguistic term into his writing on the remainder. It is this fact of corruption which reveals the essentially historical character of language, the ‘clash’ between synchronic and diachronic accounts of language renders the remainder that “part of language [which] conserves the past, witnesses to its struggles, and carries them on in the present”14 (Lecercle, 1990, pp. 182–183). Here repressive processes of signification and subjectification can be disrupted, corrupted and disobeyed (Virno, 2004, pp. 70–71); new forms of autonomy and metamorphosis emerge, and possibilities of resistance within language appear: “...the password breaks open both words and things, by being both word and thing, function and matter, itself…” (McClure, 2001, p. 207). Not a repetition of the same, but a repetition of difference. (Deleuze, 1968)

It is in this sense that slogans perform their material role. Lecercle makes an example of the C19th Luddite slogan: ‘Long live the levelution!’15 as a punning corruption of ‘revolution’ that – in addition to its alliterative memorability – “enables the militant Luddite to interpret new political ideas of the French revolution in terms of the older native tradition of the Levellers [incorporating] the two into a new political construct” (1990, p. 82). Both features, it should be said – paronomasia and etymology – remain unintelligible to the quasi-scientific linguistics of a major language.

Etymology then, as the “mirror-image” of coinages such as ‘levelution’ (Lecercle, 1990, p. 91), may therefore be suggested as a methodology for building resistance – counter-maps and counter-narratives – to forms of subjugation found within a major language. A kind of anticipatory exercise which captures the historicity of language as a way of “reappropriating, on behalf of the oppressed, the pristine meanings the oppressors are concealing from them” (Lecercle, 1990, p. 198).

However, the etymology of the remainder is specific in its recognition that “...the essential characteristic of words is not their truth, but their force.” (Lecercle, 1990, p. 199) A rhizomatic approach to etymological analysis would therefore be one that incorporates scientific or ‘major’ narratives as one among many, seeking also the minor contexts, myths, misnomers and mondegreens that serve to multiply and corrupt as inclusive disjunctions. Lecercle highlights how etymologies and terminological origin stories tend to proliferate over time: why ask which is true when we can look for the truth in each, even if it is that most unscientific truth, the truth of desire? (Lecercle, 1990, p. 261) A minor etymology would therefore be one concerned “not [with] the endless analysis of words, but knowledge of the world, as inscribed in words” (Lecercle, 1990, p. 192); in the order-words which make the world, and the pass-words to which they correspond and may be found to remake it.

In their essay on minor literatures Deleuze and Guattari criticise the desire of literary movements (even very small ones) “to fill a major language function, to offer their services as the language of the state, the official tongue” (1983, p. 27). They call on us to instead fashion the opposite dream, ‘to create a becoming-minor’, to politicise and collectivise, to stay with the rhizome and extend it.

I therefore propose an etymology not of the tracing, but of the map, the rhizome, the remainder – a counter-etymology (or etymology as counter-narrative) situated on the frontier of language as it reaches towards the extra-linguistic, and mixes with the external world (Lecercle, 1990, p. 200): a minor etymology.

d. stakes, minor etymology & resistance

Through this first question I hope to have outlined the stakes involved in any production of language – whether an individual utterance, or the legalese of state governance – on the micro- or macro-political level. Far from the received ideas of structural or scientific linguistics, we have found language to be an intensely political and historical object, not just in its use, but in its ontological composition. Language is, to use Lecercle’s turn-of-phrase, violent:

“If there is such a thing as violence in language, the term must be taken literally – not the violence of symbol, but the violence of intervention, of an event the immateriality of which does not prevent it from having material effects, effects not of metaphor but of metamorphosis.” (Lecercle, 1990, p. 227)

To arrive at such an understanding we first conceptualised language not as a communicative medium to be reconstructed scientifically, but rather a power-relation that performs rhizomatically. This power is derived from forms of overcoding or subjectification that are enacted through the major languages of scientific, cultural, economic and political institutions. However, this process of subjectification is unstable, anonymising and historically contingent, opening up the possibility for minor languages which can serve as forces of corruption and resistance. These minor languages make use of processes that sit outside of traditional understandings of linguistics – what Lecercle calls the remainder or remainder-work – such as paronomasia, sloganeering, multiple analysis and folk etymology. The concept of a minor etymology has therefore been proposed as a means of furthering this form of resistance; using the productive, historicizing methods of amateur or ‘folk-etymology’ – with its divergent, generative tendencies – as a means of corrupting major social and linguistic formations in an explicitly political project of counter-mapping and counter-narrativization.

For Foucault, it is from within the immaterial materiality of life – “as a historical production, within the very meshes of power” – that resistance is possible (Revel, 2008, p. 33). A minor etymology may therefore be used as a methodology for both understanding and reifying this immanent potentiality; for, as Deleuze and Guattari write, building the conditions to “set the oppressed character of this tongue against its oppressive character…” (1983, p. 27).

2. What is at stake in the language of production?

a. Mercurius, truth-in-language & currency

In the introduction to his famous Dictionary of the English Language, compiled in 1755, Samuel Johnson writes: “Commerce, however necessary, however lucrative, corrupts the language…” (1755). In this next section I wish to show how finance intuits, and is, in a certain sense, constitutive of the theory of language outlined above – a claim which I hope to begin outlining through the minor etymology of a common, yet complex, term: currency.

In his writing on the remainder Lecercle praises The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville – a hugely influential book, written in the early 7th Century – for its ‘folk-etymological’ character. The Etymologies show Isidore’s desire not for “the endless analysis of words, but knowledge of the world, as inscribed in words.” (1990, p. 192) For Lecercle this is characterised above all by dual origins, etymologies which tend to proliferate (1990, p. 193). As such we will make it our point of departure, both a methodological guide and an etymological resource.

In his passage on Gods of the Heathens, Isidore makes an early connection between commercial activity and the faculty of speech when describing the etymological origins of the god Mercury:

“45. Mercury (Mercurius) is translated as “speech,” for Mercury is said to be named as if the word were medius currens (“go-between”), because speech is the go-between for people. [...] 46. He is also said to preside over commerce (merx, gen.mercis), because the medium between dealers and buyers is speech.” (Barney et al., 2010, p. VIII.xi.45-xi.46)

So it is, for Isidore, that the term Mercurius derives from both ‘medius + currens’, translated into English as middle + running, giving us a sense of speech as ‘go-between’;16 and also its relationship to commerce, from association with the Latin merx meaning merchandise.

Merx is, in its own right, an illuminating term in the etymological history of currency and its connection to language, as it is the relationship between merx (merchandise) and merces (remuneration) that demonstrates both a direct etymological connection to the term commercium as well as the sociohistorical introduction of monetary exchange for services (such as the ‘trading of influence’). The novelty of this development is articulated in Benveniste’s Dictionary of Indo-European Concepts and Society: “The term [merces] denotes quite a new notion, the introduction of money into the relations between men to buy services just as one buys a commodity” (Benveniste, 2016, p. 131).17

Contemporary philologists have determined that the ‘true’ etymological origin of Mercurius is most likely this latter derivation from merx (Vaan, 2018, p. 376), which for Isidore enters primarily as a point of sociohistorical contextualisation. Such a dual origin is nevertheless doubly crucial for our purposes, as it demonstrates that the false- or folk-etymology (medius + currens) has indeed become, through Isidore, a way of reinforcing an opaque sociohistorical connection, a truth-in-language; and one, in particular, between money and speech: that ‘the medium between dealers and buyers is speech.’18 It is through such ‘truth’ that we find inscribed a path from Proto-Italic *merk-,19 via Latin merx, merces and Mercurius to currens and on to current.

The English term current is of Middle English origin, entering the language alongside a litany of Old French words after the Norman conquest of 1066. Cognate with Isidore’s medius currens (go-between), current is first recorded in the 14th Century as an adjective describing a sense of running or flowing (Oxford English Dictionary, 2023) which, by at least the mid 1600’s, morphs into currence from which we get currency.

b. private mints, creditworthiness & instrumentalism

This word currency (sometimes styled currancy) retains this sense of running, flowing and circulation, but also begins to recover the more explicit monetary and financialised contexts embedded in its history. In a 17th Century exchange of letters with the Lord Bishop of Worcester, John Locke articulates this relationship in a passage describing the process of coining words through the metaphor of the Mint:

“When the dazling Metaphor of the Mint and new mill'd Words, &c. (which mightily, as it seems, delighted your Lordship when you were writing that Paragraph) will give you leave to consider this matter plainly as it is, you will find, that the Coining of Mony in publickly authoriz'd Mints, affords no manner of Argument against private Mens medling in the introducing new, or changing the signification of old Words; every one of which alterations always has its rise from some private Mint. The Case in short is this, Mony by vertue of the Stamp, received in the publick Mint, which vouches its intrinsick Worth, has authority to pass. This use of the publick Stamp would be lost, if private Men were suffer'd to offer Mony stamp'd by themselves: On the contrary, Words are offer'd to the Publick by every private Man, Coined in his private Mint, as he pleases; but 'tis the receiving of them by others, their very passing, that gives them their Authority and Currancy, and not the Mint they come out of.” (Locke, 1699, pp. 129–130)

For Locke, words (and particularly new words), both like and unlike money, derive their authority and currency from their ‘very passing’, from their sociopolitical qualities within the public sphere, rather than their relationship to an authoritative source.20 However, as Lecercle might be keen to point out, the Mint is not an innocent metaphor in this passage, but instead a kind (or force) of metamorphosis.

In 1645, a contemporary of Locke – John Evelyn – provides an early example of a confluence or metamorphosis between currency as, on the one hand, ‘circulation’ or ‘esteem’, and on the other, a ‘paper stamped and passing for money’ (Johnson, 1755) with the introduction of the term ‘letter of credit’ (1901, p. 183).21 Credit, for the century prior to 1645, meant primarily ‘to believe’ and a ‘letter of credit’ in turn a ‘credential’, or ‘character reference’. (Hughes, 1988, p. 81) In the materialisation of a ‘letter of credit’ – which, in Evelyn’s case, guarantees international payments and withdrawals as a kind of loan – we can see how ‘private men’ are in fact ‘suffer'd to offer money stamped by themselves’, staked on their reputation.

This new instrument or currency of globalised (and globalising) trade exemplifies the manner in which processes of subjectification become bound up with processes of financialisation within language; both the discursive language of reputations and the technical, material language of promissory notes. To use Deleuze & Guattari’s terminology, we might say the order-word becomes increasingly embedded in currency – materially and functionally – especially as that currency becomes increasingly abstract.

In Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary, completed in 1755, we see, perhaps for the first time in writing, a definition of currency which fits into this picture: “The papers stamped in the English colonies by authority, and passing for money.” This point is concretised by Ian Baucom, in his book Spectres of the Atlantic, who argues that during this time the ‘decoupling of public personhood’ from both inherited, landed communities of obligation and the ‘republican practice of virtue’ leads to an “...[increasing attachment] not to the defence of local interests (and the interests of the locale) but to the speculative rise and fall of the value of paper monies…” (Baucom, 2005, p. 56). He shows how – in 18th Century Liverpool in particular – even those without a direct stake in the transatlantic slave trade or ship-building industry, ‘profited amply’ through a secondary market of bills of exchange (2005, pp. 56–62) similar in nature to Evelyn’s letter of credit.

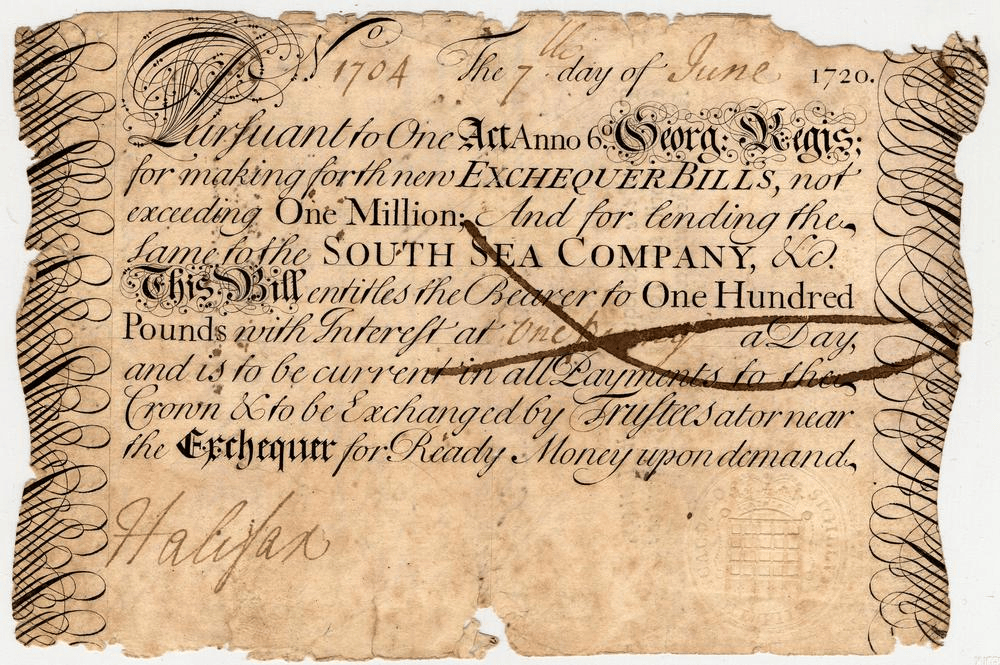

Figure 3. South-Sea Annuities certificate. (Bill of Exchange, 2023)

However, through the expansion of this exchange, “as bills travelled from one hand to another, each succeeding possessor cancelling the name of the previous holder…” he notes that a ‘double economy’ emerges: “an economy of monetary value and an economy of trust whose foundation was credibility…” (2005, p. 64). Just as Walter Benjamin shows how commodity culture is a practical expression of a particular phenomenology of things; Baucom shows how the speculative culture of finance capitalism demands more than a set of accounting protocols, but rather a practice of ‘social reading’ and ‘intersubjective analysis’, a “phenomenology of transactions, promises, character, credibility” (2005, p. 64).

In this account, the primary violence of financialisation can therefore be seen to function isomorphically to the violence of (a major) language; in the re-stratification of social (or, indeed, bare) life through the incorporeal transformations enacted and enunciated by a freshly minted, creditworthy subject. This process takes on its most extreme form in the figure of the slave, the trading of whom underwrites the process which Baucom describes – the violence of “becoming a ‘type’”, a type of nonperson, property or currency (Baucom, 2005, p. 10). By degrees such transformations then extend to the creation of wage-labourers who, as David Graeber points out, primarily “[worked] for those who had access to these higher forms of credit” such as government and mercantile debts which also “circulated as currency” (Graeber, 2011, p. 339). And so, ‘overwriting’ this system from the top, financiers then work to wield this currency of language, or rather, language as currency, among and against one another.

This last point is exemplified in the craze of the South Sea Bubble of 1720 in which traders, buoyed by the coffee-houses supplied by transatlantic winds, capitalised on this new practice of ‘social reading’ to inflate the stock price of the South Sea Company (after being granted a monopoly contract to supply the Spanish Caribbean with slaves) (Graeber, 2011, pp. 346–347) [fig.3]. In capturing the imagination of the creditworthy public the South Sea Company’s stock rose from £170 to £950 only to crash back within the span of seven months, bankrupting thousands and threatening the national economy, despite no significant changes being made in the commercial dealings of the company (Baucom, 2005, p. 92).

In each case we see the anonymising function of the major language of finance actualised through a duplicitous form or force of currency, encountered at the intersection of exchange and esteem. Returning to Locke’s original intervention, we see the distinction between public and private mints, money and words, collapse through such processes of financialisation – even those in such primordial forms.

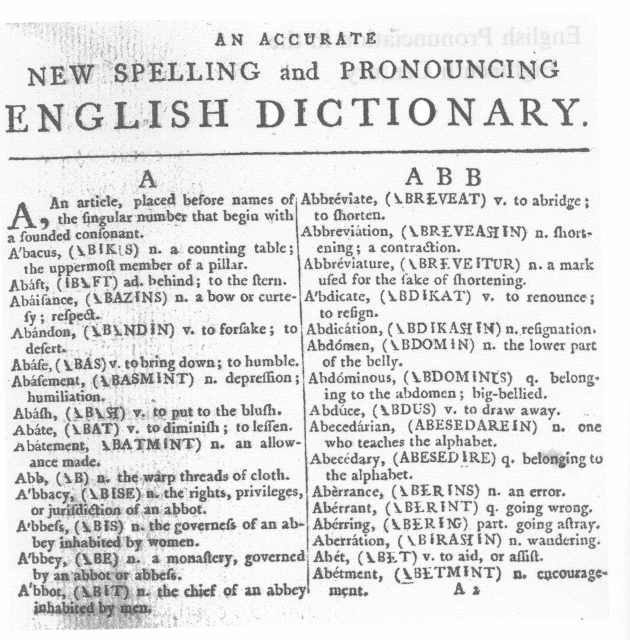

c. inkhornisms, elocution & countermarks

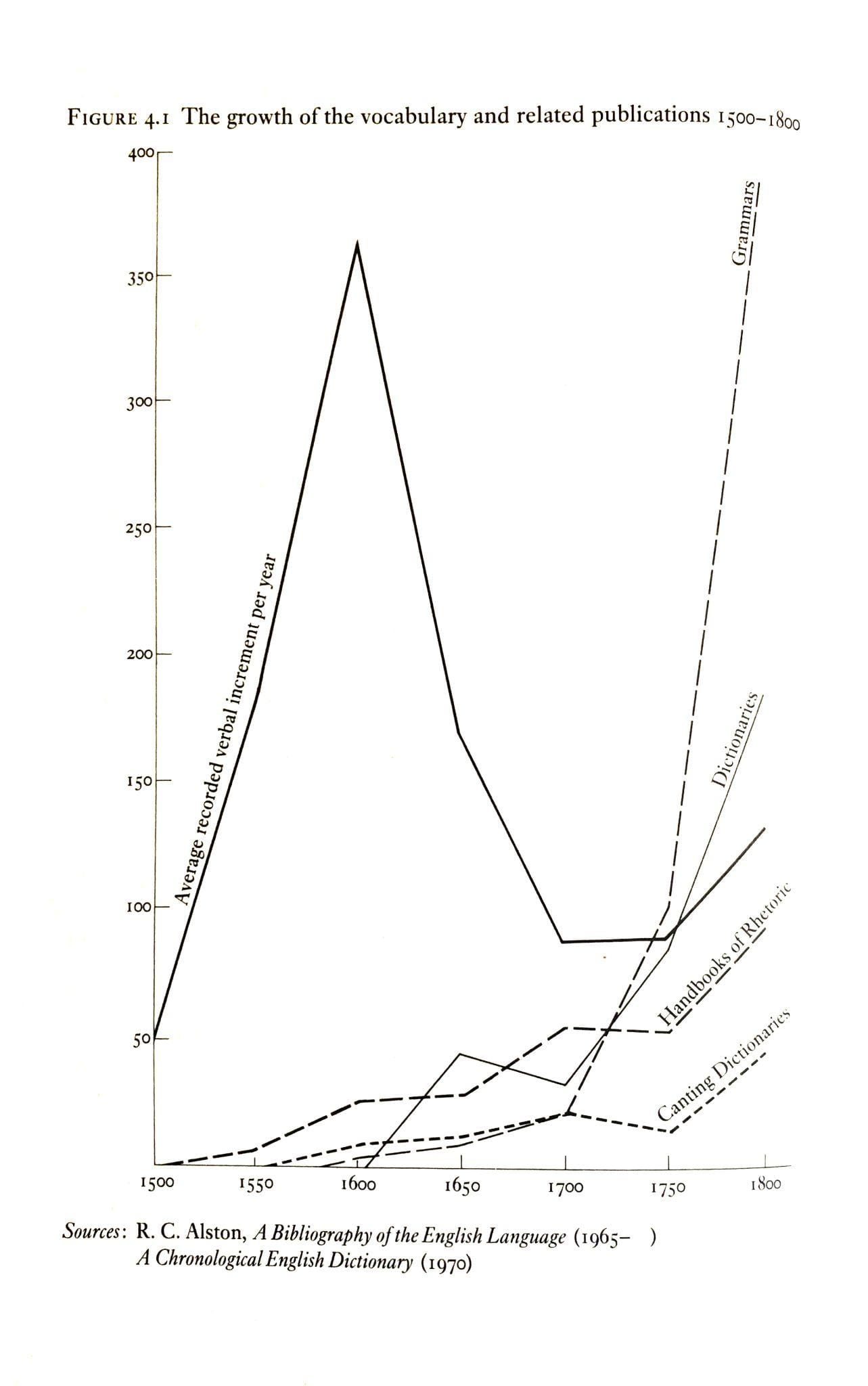

Returning momentarily to a linguistic perspective, the context for this discussion is relevant as, in the years leading up to Locke’s intervention, the infamous ‘inkhorn’ debate gave rise to various attempts at rationalising the language. Between the 16th – 17th centuries, thousands of neologisms, loan-words and ‘inkhornisms’ were introduced into English [fig.4] as: more rapid forms of printing and distribution gave rise to new translations of classic works; words became ‘borrowed’ into European dialects from colonial encounters; and developments in the ‘new’ sciences gave rise to the need for more specific technical vocabularies. (Hughes, 1988, p. 101)

Figure 4. The growth of vocabulary and related publications 1500–1800 (Hughes, 1988)

As we have seen above, and as De Certeau articulates well, it is during this period that “mastery of language guarantees and isolates a new power, a 'bourgeois' power [...] which can make language (whether rhetorical or mathematical) its instrument of production” (1984, p. 139). Obviously, such an extensive influx of new words threatens to disrupt this power, with new words opening up opportunities of social mobility and struggle for those outside this rapidly ossifying class.

To counter this, participants in the Inkhorn Controversy – men of letters such as Sir John Cheke, Ralph Lever and Edmund Spenser – proposed various measures to purify and simplify the language in its transition from Middle to Modern English. (Hughes, 1988, p. 103) As a consequence of this effort we see an explosion in the production of dictionaries, books of grammar and handbooks of rhetoric in the 18th Century [fig.3], many of these serving to define not only the language, but also “the code governing socioeconomic promotion [which] dominates, regulates, or selects according to its norms all those who do not possess this [particular] mastery of language.” (De Certeau, 1984, p. 139) It is in this sense that Johnson writes of commerce’s ‘corruption’ of the language, as it introduces new words and variability which cannot be contained. However, as can be expected, it is in the ‘minor’ end of such debate that we find resistance to this very explicit project of establishing a currency on which reputation can be traded – the establishment of a ‘major language’ – from two 18th Century contemporaries, the actor Thomas Sheridan and the radical Thomas Spence.

In a characteristically pithy critique of Locke’s account of language, the Irish stage actor and educator, Thomas Sheridan, wrote in 1762 he had “not a little contributed to the confined view which we have of language, in considering it, as made up wholly of words.” (Ulman, 1994, p. 155) What, for Sheridan, Locke and others following him missed out from their account of language were the embodied aspects of speech; emotion and elocution. Prefiguring, in some ways, Lecercle’s claims for the remainder, Sheridan continues, “…the nobler branch of language, which consists of the signs of internal emotions, was untouched by him as foreign to his purpose.” (Ulman, 1994, p. 155)

Inspired by Sheridan’s critique, and the extraordinary popularity of his lectures on elocution (Mahon, 2001; Beal and Gupta, 2023), Thomas Spence created his own dictionary in 1775; the first in English to include a phonetic transcription [fig.5] which was intended to make it easier for the illiterate to learn to read and write (Thomas Spence, 2023). Far from debates of Latin roots and increasingly problematic nationalist arguments over the King’s English (Hughes, 1988, p. 104), Spence focused proactively on harnessing this newly invested power within language, and mobilising it in the interest of the most immiserated members of an increasingly ‘enclosed’ society.

Figure 5. Excerpt from Thomas Spence’s Grand Repository of the English Language (Beal and Gupta, 2023)

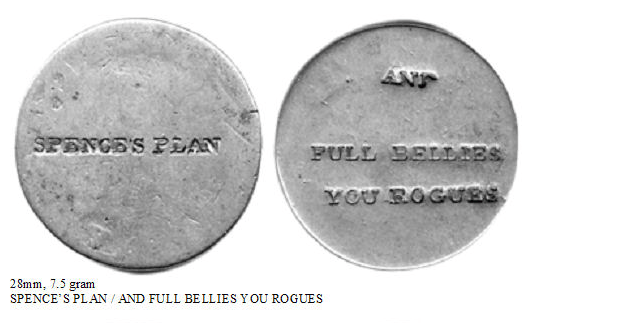

Within this etymology however, the radical edge of Spence’s philosophy is captured most strikingly not in his dictionary but in his countermarks [fig.6–9] – in his direct interventions onto the surface of the currency to which he was opposed, and, in turn, the creation of his own. Here again, as with ‘levelution’ we see the force of the slogan materialised – SPENCE’S PLAN AND FULL BELLIES YOU ROGUES – and a collapsing or corruption of the distinctions between meanings within the word currency.

Here, we begin to see how currency catalyses its immanent, minor multiplicities: “SPENCE’S PLAN” becomes a pass-word, not only the catch-phrase for a utopian society predicated on common ownership, but one distributed via a reappropriation of the languages and material cultures such a society seeks to resist.

Figure 6. SPENCE’S PLAN / AND FULL BELLIES YOU ROGUES (Beal and Gupta, 2023)

Figure 7. SMALL FARMS / AND LIBERTY (Beal and Gupta, 2023)

Figure 7. STARVATION / PLENTY (Beal and Gupta, 2023)

Figure 8. OURS / OURS (Beal and Gupta, 2023)

d. conclusion

Above all, through this question, I hope to have begun showing how the work of a ‘minor etymology’ might proceed.

Taking currency as our starting point we have shown how multiple analysis, or folk-etymology, might be used productively to uncover historic truths embedded in language; in this case uncovering not only the historic connection between speech and exchange, but also the nature of that exchange extending beyond commodities into social forms of labour. Proceeding ‘rhizomatically’, we examined the way in which metaphors of ‘coining’ words through either public or private mints prefigured material changes in processes of subjectification at the dawn of modern capitalism. Moving incrementally back and forth in time, we have shown the inclusive disjunctions which constitute currency, and how, in establishing finance as a major language, the violence of language becomes co-constitutive with the violence of financialisation. Lastly, we sought to contextualise this becoming-major of finance through the inkhorn controversy, and identify areas of development within this notion of currency that serve as forms of resistance to finance. This last point shows how minor etymology may need to move away from more-or-less strict linguistic analysis entirely, into analyses of material cultures as well. The guiding thread, the ‘line of flight,’ however, between these vignettes is a focus not so much on the communicative elements of currency (and language more broadly), but instead its socio-political force.

Secondly, I hope to have shown how repressive processes of subjectification facilitated by and within language are worsened through the continued development of financialization. While the counter-narrative presented above has extended only so far as the late 18th Century, these problems have continued unabated into the 21st. In his book A Grammar of the Multitude, Paulo Virno highlights the effects of a growing importance of language in contemporary work and life, writing that “contemporary production becomes ‘virtuosic’ (and thus political) precisely because it includes within itself linguistic experience as such” (2004, p. 56); that, today, capitalist production increasingly integrates the “exploitation of the very faculty of language” (2004, p. 68) which contributes to an ever-greater part of the productive process. The task of the minor etymology has thus become more important than ever, to fashion ‘the opposite dream’, ‘to create a becoming-minor’, to politicise and collectivise, to stay with the rhizome and extend it.

Bibliography

Althusser, L. (1970) ‘Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses 1969-70’. Available at: https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/althusser/1970/ideology.htm (Accessed: 29 March 2023).

Augustine (1963) City of God. Translated by W.M. Green. Harvard University Press. Available at: https://www.loebclassics.com/view/augustine-city_god_pagans/1957/pb_LCL412.425.xml.

Austin, J.L. (1962) ‘How to do Things with Words’.

Barney, S.A. et al. (2010) The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville. Cambridge University Press.

Baucom, I. (2005) Spectres of the Atlantic.

Baudrillard, J. (1983) Simulacra and Simulation.

Beal, J. and Gupta, A.F. (2023) English & Tokens. Available at: https://www.thomas-spence-society.co.uk/english-tokens/ (Accessed: 27 April 2023).

Bell, S. (2001) ‘The Role of the State and the Hierarchy of Money’, Cambridge Journal of Economics, 25(2), pp. 149–63.

Benveniste, É. (2016) Dictionary of Indo-European Concepts and Society. Translated by E. Palmer.

Bill of Exchange (2023) The British Museum. Available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/C_CIB-54397 (Accessed: 27 April 2023).

Breland, A. (2021) ‘How an era of financial precarity set the stage for crypto’, Mother Jones, May. Available at: https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2021/11/who-goes-crypto-eth-bitcoin-etc-financialization-gamestop-class-wealth/ (Accessed: 22 February 2023).

Bryant, L. (2011) ‘Two Types of Assemblages’, Larval Subjects ., 20 February. Available at: https://larvalsubjects.wordpress.com/2011/02/20/two-types-of-assemblages/ (Accessed: 15 April 2023).

Culp, A. (2016) Dark Deleuze.

De Certeau, M. (1984) The Practice of Everyday Life.

Deleuze, G. (1968) Difference and Repetition.

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (1983) ‘What Is a Minor Literature?’, Mississippi Review. Translated by R. Brinkley, 11(3), pp. 13–33.

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (1987) A Thousand Plateaus.

Evelyn, J. (1901) The Diary of John Evelyn. Available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/41218/41218-h/41218-h.htm (Accessed: 26 April 2023).

Finlayson, A. (2009) ‘Financialisation, Financial Literacy and Asset-Based Welfare’, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 11(3), pp. 400–421. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-856X.2009.00378.x.

Foucault, M. (1971) ‘The Order of Discourse’.

Foucault, M. (1982) ‘The Subject and Power’, Critical Inquiry, 8(4), pp. 777–795.

Graeber, D. (2011) Debt, The First 5,000 Years. Available at: https://www.mhpbooks.com/books/debt/ (Accessed: 22 February 2023).

Grisham, T. (1991) ‘Linguistics as an Indiscipline: Deleuze and Guattari’s Pragmatics’, SubStance, 20(3), pp. 36–54. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/3685178.

Grose, F. (1811) Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue. Available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/5402 (Accessed: 26 February 2023).

Haiven, M. (2018) Art after Money, Money after Art. Available at: https://www.plutobooks.com/9780745338248/art-after-money-money-after-art (Accessed: 22 February 2023).

Hughes, G. (1988) Words in Time. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell (The Language Library).

Jameson, F. (1981) The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act. 1st edn. Cornell University Press. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctt1287f8w (Accessed: 22 February 2023).

Johnson, S. (1755) A Dictionary of the English Language. The British Library. Available at: https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/samuel-johnsons-a-dictionary-of-the-english-language-1755 (Accessed: 29 March 2023).

Lecercle, J.-J. (1990) The Violence of Language. Available at: https://www.routledge.com/Routledge-Revivals-The-Violence-of-Language-1990/Lecercle/p/book/9781138226715 (Accessed: 21 February 2023).

Locke, J. (1699) Mr. Locke’s reply to the right reverend the Lord Bishop of Worcester’s answer to his second letter wherein, besides other incident matters, what his lordship has said concerning certainty by reason, certainty by ideas, and certainty of faith, the resurrection of the same body, the immateriality of the soul, the inconsistency of Mr. Locke’s notions with the articles of the Christian faith and their tendency to sceptism [sic], is examined. Available at: http://name.umdl.umich.edu/A48890.0001.001.

Lorey, I. (2015) State of Insecurity: Government of the Precarious. Translated by A. Derieg. Verso Books, p. 148.

Mackenzie, D. (2006) ‘Is Economics Performative? Option Theory and the Construction of Derivatives Markets’, Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 28(1), pp. 29–55. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10427710500509722.

Mahon, M.W. (2001) ‘The Rhetorical Value of Reading Aloud in Thomas Sheridan’s Theory of Elocution’, Rhetoric Society Quarterly, 31(4), pp. 67–88.

Malik, S. and Phillips, A. (2012) ‘Tainted Love: Art’s Ethos and Capitalization’.

Marazzi, C. (2008) Capital and Language. Available at: https://mitpress.mit.edu/9781584350675/capital-and-language/ (Accessed: 21 February 2023).

Martin, R. (2002) Financialization Of Daily Life. Temple University Press. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt14bsxq4 (Accessed: 19 February 2023).

McClure, B.D. (2001) Deleuze-Guaftari’s Pragmatics of the Order-Word. University of Warwick, Department of Philosophy.

Nitzan, J. and Bichler, S. (2009) Capital as Power: A Study of Order and Creorder. Available at: https://www.routledge.com/Capital-as-Power-A-Study-of-Order-and-Creorder/Nitzan-Bichler/p/book/9780415496803 (Accessed: 22 February 2023).

Oxford English Dictionary (2023). Oxford University Press. Available at: https://www.oed.com/ (Accessed: 15 April 2023).

Revel, J. (2008) ‘The materiality of the immaterial: Foucault, against the return of idealisms and new vitalisms: Dossier: Art and Immaterial Labour’, Radical Philosophy [Preprint], (149). Available at: https://www.radicalphilosophy.com/article/the-materiality-of-the-immaterial (Accessed: 18 March 2023).

Skelton, J. (1499) ‘The Bowge of Courte’. Available at: https://www.luminarium.org/editions/bowge.htm (Accessed: 12 March 2023).

Thomas Spence (2023). Available at: https://www.marxists.org/history/england/britdem/people/spence/index.htm (Accessed: 27 April 2023).

Thompson, E.P. (1963) The Making of the English Working Class.

Tomkis, T. (1615) Albumazar A comedy presented before the Kings Maiestie at Cambridge, the ninth of March. 1614. By the Gentlemen of Trinitie Colledge. Available at: http://name.umdl.umich.edu/A13802.0001.001.

Ulman, H.L. (1994) Things, Thoughts, Words, and Actions: The Problem of Language in Late Eighteenth-century British Rhetorical Theory. SIU Press.

Vaan, M. de (2018) Etymological Dictionary of Latin and the other Italic Languages. Leiden · Boston, 2008.

Virno, P. (2004) A Grammar of the Multitude. Available at: https://mitpress.mit.edu/9781584350217/a-grammar-of-the-multitude/ (Accessed: 21 February 2023).

Footnotes

-

In the original French Deleuze & Guattari use Mot d’ordre, which can also be translated as slogan or password (in a similar sense to the English militaristic watchword)which we will see later. ↩

-

“‘I sentence you to…’ For Deleuze and Guattari, this is a speech act; as a performative statement, it accomplishes the act by speaking. But it does not do so because it refers to other statements or external acts; it does so because it is socially and politically empowered by them. It is empowered by what Oswald Ducrot has called ‘implicit or nondiscursive presuppositions,’ in this case, those relating to a whole juridical apparatus that distributes subjectifications, meeting in the figure of the judge.” (Grisham, 1991, p. 45) ↩

-

Here we might think of the moralization of status words in Middle English, as discussed by Geoffrey Hughes; where terms of address or rank such as noble, gentle, frank, free and liberal or conversely, villain, knave or churl become terms of moral conduct. (Hughes, 1988, pp. 44–45) ↩

-

See also the Will to Truth in Foucault (1971) ↩

-

The effect of this change in emphasis is no more evident than in discussions on the field of linguistics itself. As Deleuze & Guattari write, the “scientific model taking language as an object of study is one with the political model by which language is homogenized, centralized, standardized, becoming a language of power, a major or dominant language…” (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987, p. 117); "linguistics itself is inseparable from an internal pragmatics involving its own factors.” (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987, p. 106) ↩

-

As we will see later, orders of discourse are achieved through the use of order-words – the enunciation of performative statements that indirectly codify the proper terms of reference (i.e. in the academy, or the economy), or standard forms of language (i.e. Standard English). ↩

-

As Lecercle says: “...the rules of grammar are to be thought of not in terms of the laws of the physical universe, but rather in terms of frontiers.” (1990, p. 18) ↩

-

Here Foucault is playing on the dual sense of the word ‘subject’ – employing at once the idea of subjectivity (one's conscience, identity or ‘self-knowledge’) and subjugation (to be subject to someone else) – emphasising the constitutive relation between these two meanings. (1982, p. 781) ↩

-

This sense of pre-individuality is well articulated also by Paolo Virno: “Language, however, unlike sensory perception, is a pre-individual sphere within which is rooted the process of individuation [... when] the prevailing relation of production is pre-individual [...] we face also a pre-individual reality which is essentially historical.” (Virno, 2004, p. 77) ↩

-

It is perhaps in this spirit that Deleuze and Guattari open A Thousand Plateaus with the famous lines: “The two of us wrote Anti-Oedipus together. Since each of us was several, there was already quite a crowd.” (1987, p. 1) ↩

-

For a less radical variation see Paolo Virno on Simondon in A Grammar of the Multitude: “The subject is, rather, a composite: ‘I,’ but also ‘one,’ unrepeatable uniqueness, but also anonymous universality.” (2004, p. 78) For a more radical one, see Andrew Culp on the concept of ‘Un-becoming’ (2016, pp. 26–28) ↩

-

Or, in Lecercle’s translation, a collective arrangement of utterance. ↩

-

“Every order-word, even a father's to his son, carries a little death sentence—a Judgment, as Kafka put it.” (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987, p. 89) ↩

-

For Lecercle, borrowing again from Deleuze and Guattari, this reveals the a-synchronic temporality of language – the inextricable mix of variation and continuation that constitutes language. (Lecercle, 1990, p. 186) ↩

-

The ‘violence of language’ goes both ways; see also, in The Making of the English Working Class: “The Levelution is begun, / So I'll go home and get my gun, / And shoot the Duke of Wellington.” Belper street-song (Thompson, 1963) ↩

-

This interpretation is strengthened in Isidore’s original text by a false-etymology between the Greek Ἑρμῆς (for the Greek god Hermes, to whom Mercury is a Roman counterpart) and ἑρμηνεία (meaning interpretation) not quoted above. (Barney et al., 2010, p. VIII.xi.45-xi.46) ↩

-

Benviniste, who originates this connection, provides some similarly relevant ideas of what such services may have been: “What merces remunerates is not the result as such of a working man’s labor, but the sweat of his brow, the soldier’s service in war, the skill of a lawyer and furthermore, in public life, the intervention of a politician, what one would call a trading of influence.” (Benveniste, 2016, p. 130) ↩

-

It seems likely to me that Isidore takes this understanding from book VII of St Augustine’s ‘City of God’ – written in the 5th Century – which bears a strikingly similar resemblance: “But perhaps speech itself is called ‘Mercury,’ as the explanation of his name seems to show. For he is said to have been named Mercury as being a middle courier (medius currens), because speech runs like a courier between men. Hence he is called Hermes in Greek, since speech, or interpretation, which certainly belongs to speech, is called hermeneia. Hence also he is in charge of trade, since between sellers and buyers speech occurs as a medium. The wings on his head and feet mean that speech flies through the air like a bird. He is called a messenger, since language is the messenger that proclaims our thoughts. If therefore Mercury is speech itself, by their own admission he is no god.” (Augustine, 1963, p. 412) ↩

-

Proto-Italic. *merk- 'trade, exchange'. All derived from a stem *merk- also found in Faliscan and Oscan. The god Mercurius was probably the god of exchange. (Vaan, 2018, p. 376) ↩

-

Here we see, in miniature, a debate which continues to play out within economics between metallist and chartalist accounts of monetary value. ↩

-

“We went hence from Leghorn, by coach, where I took up ninety crowns for the rest of my journey, with letters of credit for Venice, after I had sufficiently complained of my defeat of correspondence at Rome.” ↩